3. SNCF under the control of the German occupying forces

The Armistice Agreement

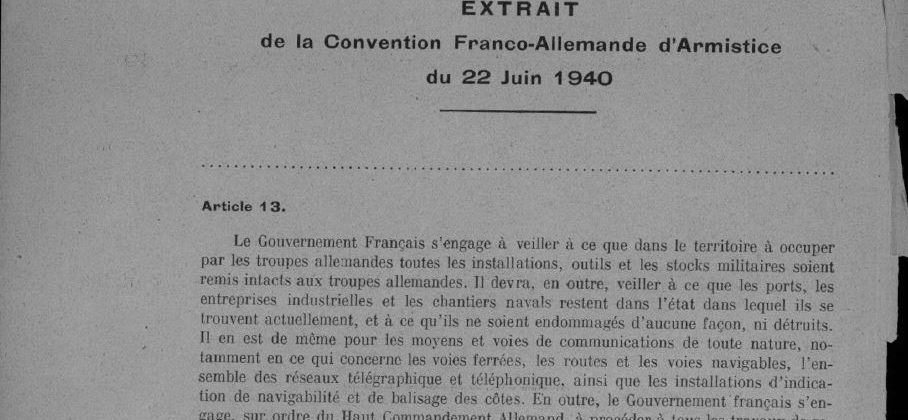

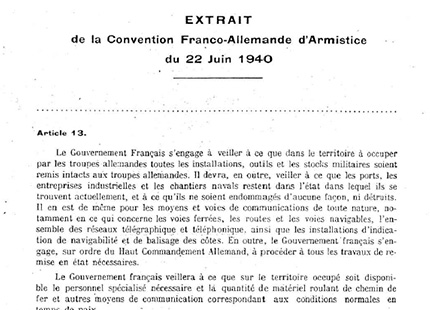

The French government, led by Marshal Pétain, President of the French Council of Ministers, signed the Armistice Agreement with Germany in Compiègne on 22 June 1940. The terms of the German occupation were intended to neutralize French military forces. The country was carved in several zones. On one side of the dividing line stood the German-occupied zone—a full three-fifths of continental France by area, and home to two-thirds of its rail network. On the other stood Vichy-controlled France, where the Nazis oversaw the day-to-day running of the railways following the 11 November 1942 invasion and prioritized their own needs, leading to major disruption.

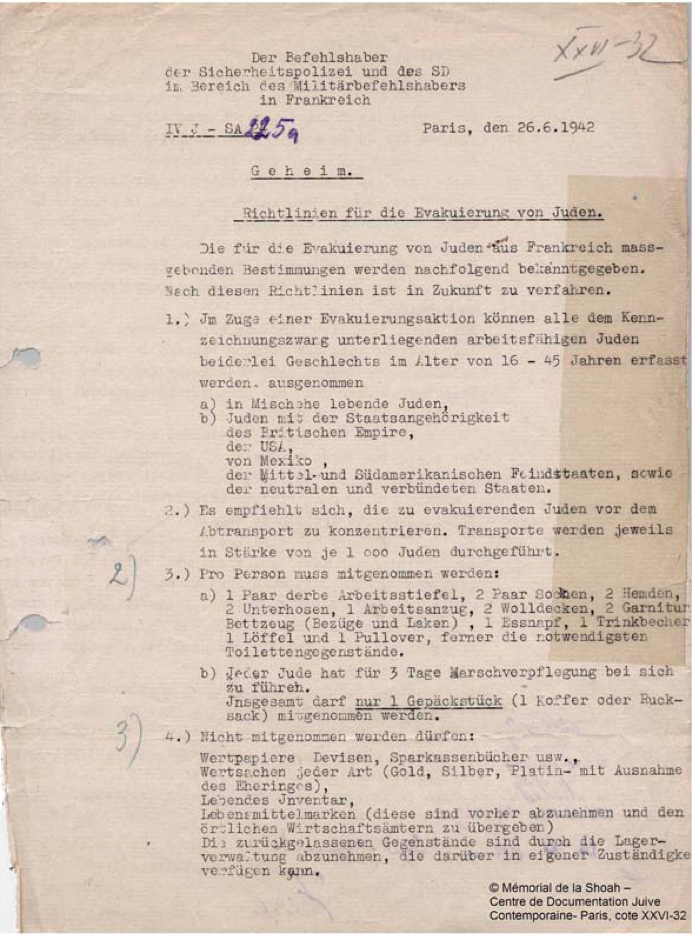

In theory, France retained sovereignty over its entire territory. But in practice, Germany exercised the rights of an occupying power in the occupied zone, leaving the French authorities with no option but to collaborate. The rail network was now under the command of the German Army’s Transport Chief. Under Articles 13 and 15 of the Agreement, France’s railways were placed at his “full and entire disposal”. French transport law could “be repealed or amended solely with authorization from or by order of the German Transport Chief”, who was vested with the power to “take whatever measures he considers appropriate for operational and traffic management reasons”.

The fall of France marked the beginning of four years of Nazi occupation, during which time SNCF would grapple with the complex demands and pressures of operating under the control of two governments and adhering to the terms of the Armistice Agreement.

Rail workers under duress

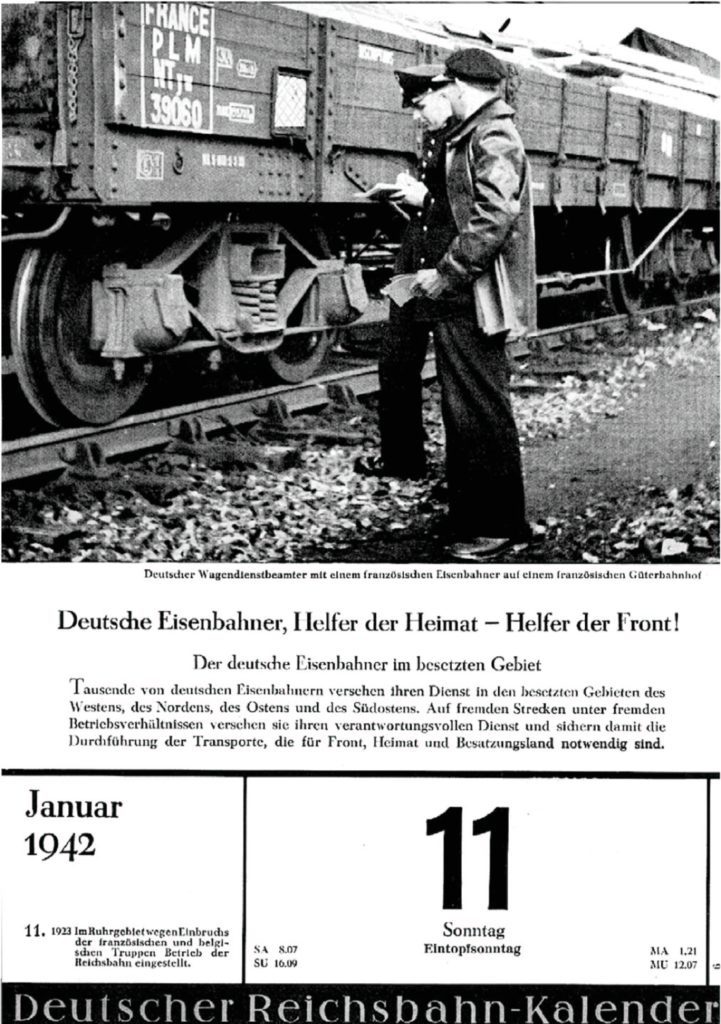

In 1940, SNCF was the largest French employer by headcount, with half a million workers and a network stretching to 42,000 km of track. On July 15 that year, the company’s fortunes took a dramatic turn when the WVD set up operations in Paris.

Three days later, German transport minister Julius Dorpmüller, who also served as general manager of the Reichsbahn, arrived in the city by train. At Paris-Est station, he delivered a stirring speech to assembled military rail workers from the WVD, praising them for their speed in reopening rail lines between the French capital and Nazi Germany.

Under the Vichy government’s policy of collaboration, the railways remained under French control. But the WVD positioned German rail workers in stations, depots and other rail facilities, where they were responsible for overseeing French rail workers as they continued to run the network – and for ensuring that all transport services required by the occupiers were given absolute priority. By the end of 1940, close to 10,000 German workers were working in the French rail system, and there would be more than 30,000 by the time of the Normandy landings in 1944.

SNCF’s organizational chart was changed to include a German supervisory entity at every level.

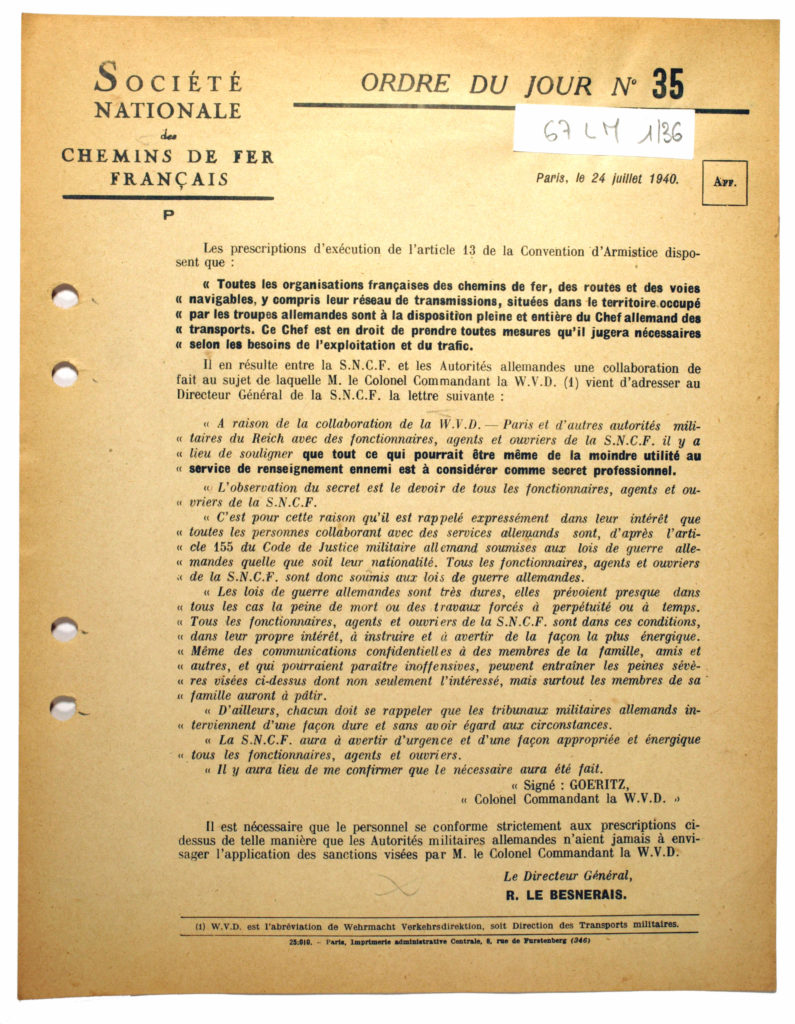

Order No. 35 of July 24, 1940, an internal directive posted in all SNCF facilities, publicized a letter by Colonel Göritz, commandant of the WVD, clarifying the relationship between SNCF employees and the Nazi authorities under Article 13 of the Armistice Agreement. The letter confirmed that “all French rail organizations (…) are placed at the full and entire disposal of the German Transport Chief” and that “pursuant to Article 155 of the German Code of Military Justice, all persons collaborating with the German services are subject to German military law, irrespective of their nationality”. Göritz also sounded a note of warning to SNCF employees, reminding them that “German military law is very harsh: in nearly every case, it calls for the death penalty or hard labour, for life or for a specific term”.

Rolling stock and personnel requisitioned

SNCF continued operating the French rail network under these challenging conditions, carrying essential goods, displaced people, and military supplies

within and between the occupied and unoccupied parts of France. The demands on the state-owned rail company were overwhelming, especially at a time when equipment and personnel were in short supply. The Nazis, who had already seized thousands of wagons prior to the fall of France, issued repeated and pressing demands for more rolling stock. In autumn 1940 alone, SNCF was instructed to hand over 2,000 locomotives and 85,000 wagons to the Germans.

The war effort also created an insatiable demand for labour: in February 1941, the Reichsbahn called for 5,000 drivers and 6,000 maintenance workers familiar with the recently requisitioned French locomotives, forcing SNCF to recruit volunteers and train outside hires. But there were other reasons for the labour shortage: scores of rail workers were being held at POW camps in Germany, 1,200 were suspended or sacked as part of the government-initiated clampdown on communists, 80 or so were dismissed under anti-Jewish legislative measures, and many more were arrested and imprisoned by the French and German authorities.

From 1943 onwards, the Nazis stepped up the pace of deportations, placing extra strain on an increasingly fragile network. In September alone, the French railways endured 60 aerial bombings, 150 machine-gun attacks and 330 ground-based assaults.

The Germans grew more demanding as time wore on. In the last few months of the war, as the emphasis shifted from control to execution and suppression, the occupying authorities sought more influence over the day-to-day running of the company—in part because Germany’s military might was waning, and in part because they no longer trusted French managers.

Learn more: The SNCF Under German Occupation: 1940–1944 (Bachelier Report), 1996 (in French).

Political deportations and the Holocaust in France

Starting in 1942, the WVD used the French rail network to transport Jews and so-called “political” deportees to camps in the Reich. Although decisions were handed down from Berlin, the Vichy government and its police forces became accomplices in the deportations.

The first two convoys of Jewish deportees left Compiègne in northern France for Auschwitz on March 27 and June 5, 1942. Soon after, thousands more were loaded onto trains bound for German camps—first from Le Bourget near Drancy transit camp and, from the summer of 1943, from the repurposed freight yards in Bobigny. In total, 75,721 Jews—including 11,400 children—were deported from France during the war. Their names are listed in a commemorative book by historian Serge Klarsfeld. Only 5.2% of the deportees lived to see the end of the war.

On July 6, 1942, the first train carrying political deportees—mostly communists—pulled out of Compiègne station, again bound for Auschwitz. The Nazis carried out mass deportations of political prisoners and Resistance members from January 1943 onwards. Some were transported in small groups to German prisons. In contrast, others went in 28 large convoys—each carrying one to two thousand people—to concentration camps at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Mauthausen, Natzweiler-Struthof, Neuengamme, Ravensbrück (exclusively for women), and Sachsenhausen, as well as to smaller satellite camps.

According to research by the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Déportation, around 88,000 people were deported because they engaged in Resistance efforts, because they spoke out against the occupying forces, or because they held views the Nazis and their collaborators considered dangerous. The figure also included hostages, common criminals and people rounded up by the authorities. Over 40% of these deportees are estimated to have died.

Under the terms of the Armistice Agreement, the French authorities were responsible for operating the railways under German supervision. In practice, this meant that SNCF employees—at the order of Nazi officials—formed the convoys and drove them to Novéant-sur-Moselle, a town in the de facto annexed Moselle region that stood on the wartime border with Germany. On arrival, the French rail workers disembarked and handed control to their German counterparts before heading back to Paris.

The occupying authorities oversaw deportation operations with an iron fist, even resorting to violence on occasion. So while attempts were made to delay or stop these so-called “special convoys”, such endeavours were difficult to execute—and ultimately fruitless.

The Nazis were still trying to send deportees to the Reich as late as the summer of 1944—mere months before the end of the occupation and at a time when the French railways had been decimated by aerial bombings and sabotage attacks.